Erasure as Creative Gesture

Saj Issa is a young artist based in Los Angeles whose work tackles issues including capitalism and climate change, the diasporic experience, violence, and cultural erasure. Issa typically, but not exclusively, works in ceramics as the core of a practice where cultural clashes are sited within a reduced narrative content. On first view her works appear formalist in nature, and then reveal social criticism as one looks closer at the details and processes that she employs.

Issa’s parents emigrated to the US in the 1980s and worked blue collar jobs. Born and raised in St. Louis, the artist moved between the West Bank of Ramallah, Palestine, and Missouri, a Midwestern industrial state, in her youth. These two cultural touchstones, seemingly in great contrast, are evident in her work: she engages with methods and decorative patterns that recall Middle Eastern and Far Eastern decorative art, while juxtaposing western brands and logos that are immediately recognizable to any contemporary audience regardless of class or gender.

Social commentary is an abiding aspect of Issa’s practice. During the pandemic Issa created Sanitary Flask Series (2020), consisting of small ceramic sculptures of the ubiquitously desired antibacterial hand liquid, a scarce commodity that escalated in price during the initial year of COVID19. In her series, Purell becomes Purhell that Kills 99.9% of Germs and Souls. Larger and more complex sculptures created by the artist include Men Look at Women, Women watch Men Look at Them (2020), a vanity table made of industrial steel with a diamond plate motif symbolic of heavy industry. Porcelain ceramic objects mixed with stains to match the artist’s complexion are embossed with the same pattern and placed on the surface of the vanity, which itself is an abiding theme throughout art history. Issa’s objects—bra, knickers, sanitary pads, deodorant, etc—recall earlier generations of feminist art that unveiled the everyday experience of women, for example Judy Chicago’s (b 1939) Womanhouse Menstruation Bathroom 1972 or the sculptural works of Brazilian artist Nazareth Pacheco (b 1961) that include razor blades and other found mass-produced objects. In Issa’s installation, the vanity mirror is etched with an Arabic statement that aligns with the title of the work: “exhale the air I’d unwillingly shared with you” is a phrase derived from notes in the artist’s sketchbook. Her work may be considered as a contemporary distillation of the Rogers and Hammerstein song from the South Pacific, ‘I’m gonna wash that man right out of my hair’, which in 1980 was appropriated into the jingle ‘I’m gonna wash that grey right out of my hair’ for a Clairol shampoo commercial. Indeed, popular feminism was often and is still incorporated into brand marketing to sell products to the masses.

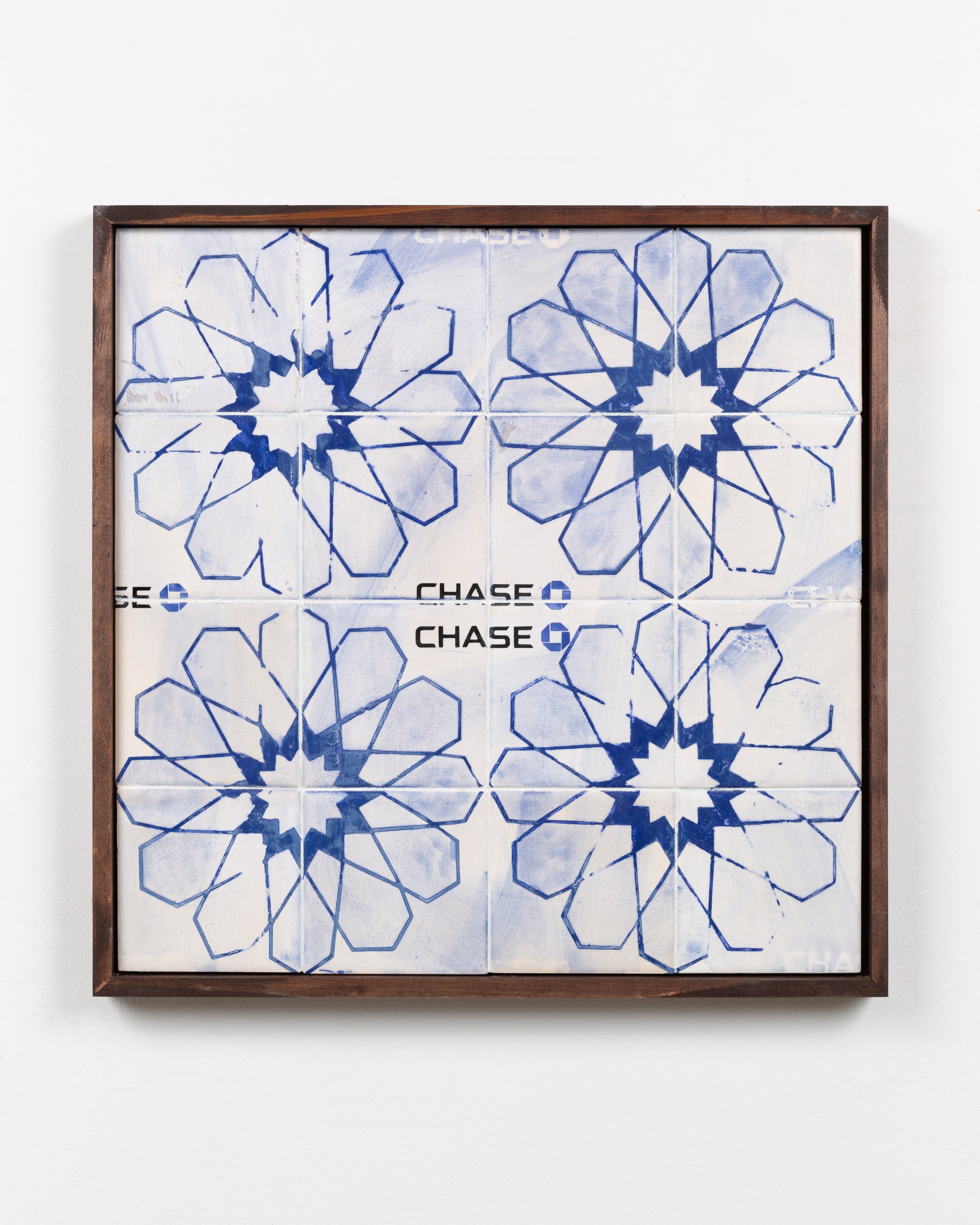

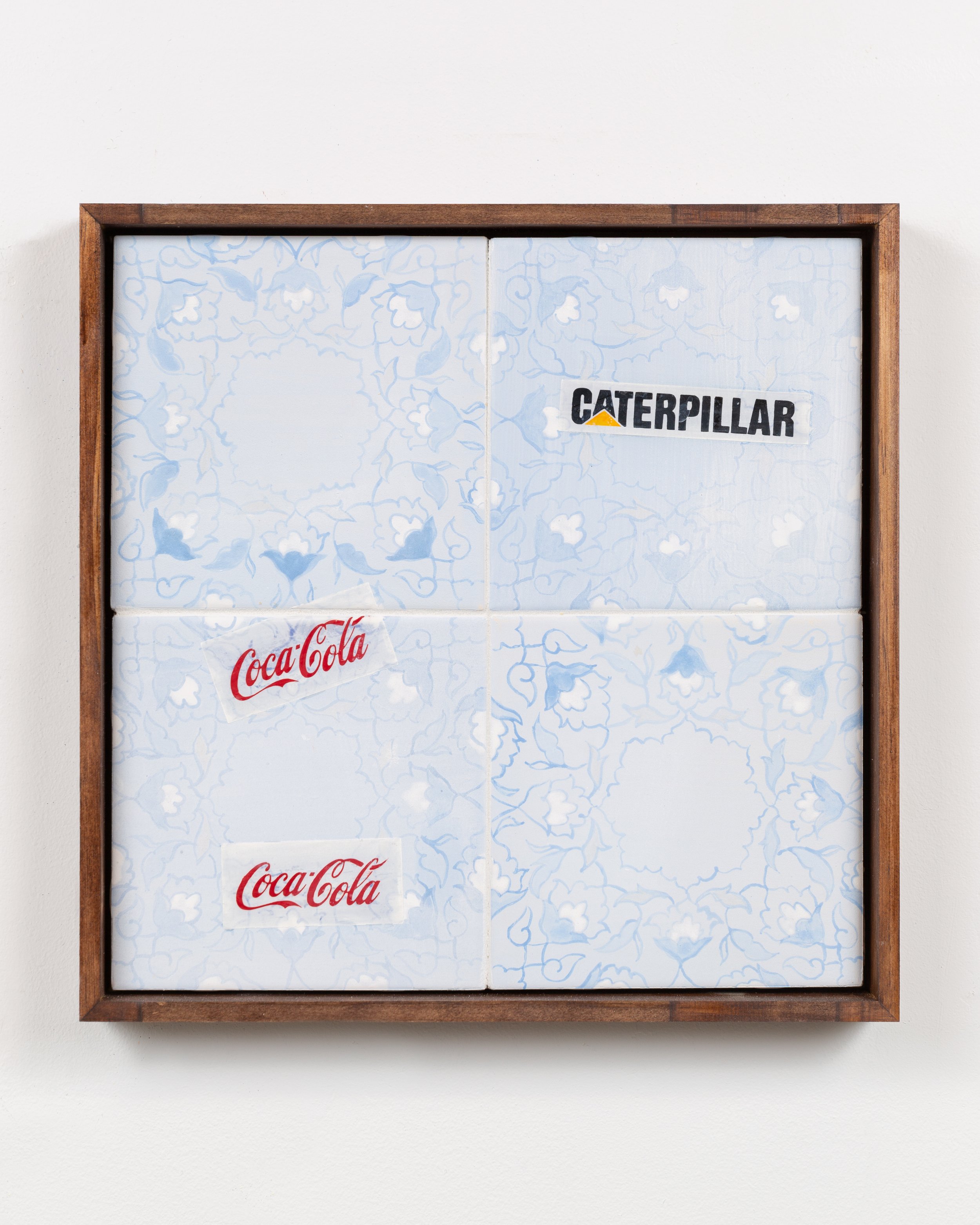

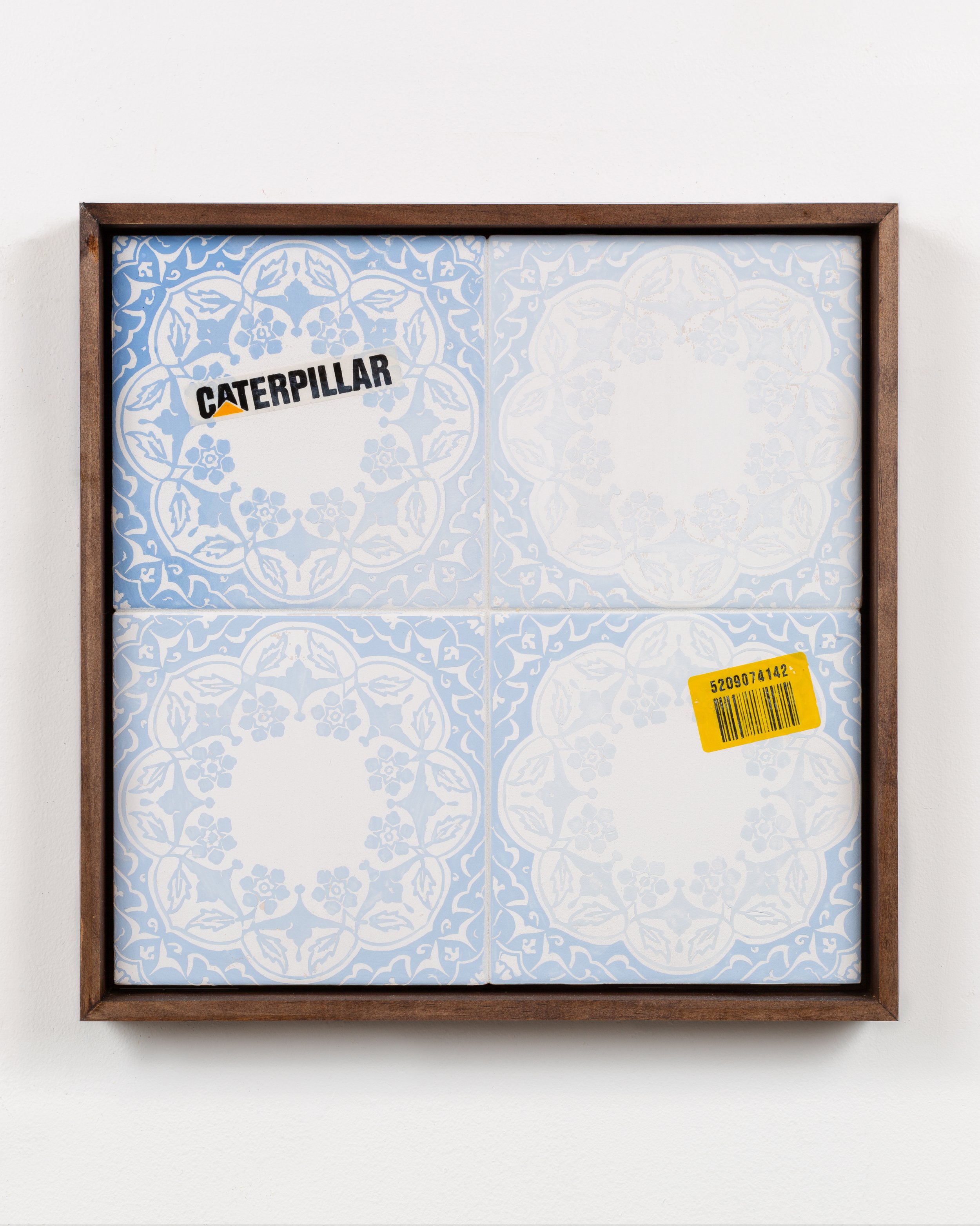

The artist is interested in late capitalism and its violence, and how brand intervention in societal spaces has contributed to the cultural erasure of diasporic communities. Issa’s recent work continues her abiding interest in pattern. The Americana Hammam series consists of wall based two-dimensional works that feature silkscreened and hand painted patterns on ceramic tiles with corporate logos on the surface. Her newest creations in this series are titled Bleach Scapes (2022) for their appearance of having been bleached by the sun, typical of architectural ornamentation that has been faded by UV exposure. The blue patterns are appropriated from traditional vessels and tiles from countries including Turkey, Palestine, and China while the logos are iconic brands well familiar to a global audience. The artist chooses the brands—Nike, Caterpillar, Chase, Coca Cola—for their lax corporate policies around global warming and climate change, thus exposing to viewers how we are all implicated in this crisis.

Issa begins these works using Illustrator software to draw a draft of the composition. Then she creates a metal screen, which is screen printed onto each individual tile. Issa’s relationship with ceramics has always been a ritual of repetitive process so she notes that it feels natural to be on a “factory mode cycle” when she created these. Once the tiles are joined together Issa takes a wet sponge and wipes at the ornamental detail. Scrubbing disrupts the pattern and inserts a gestural impulse that aligns with the artist’s interest in Abstract Expressionism. Issa posits that the gesture represents the erasure of the place of origin of the architectural patterns that she appropriates. Issa is interested in how the transaction of materials can influence cultural motifs.

For example, blue and white Delftware is originally derived from Chinese ceramics, an example of a colonial era in which cultural plundering was not questioned, at least by those in power. Aristocratic elites owned these fine objects, which were created by anonymous, low paid laborers. The artist says she was thinking about “what becomes clear when erasure happens”. This an impulse that can be aligned with feminist ideology, in particular the writer bell hooks who popularized intersectional feminist theory. In Issa’s case the intersectionality would include capitalism, cultural heritage, and gender.

Issa’s interest in Turkish ceramics was solidified during a trip to Iznik, the center of the ceramic industry in the country, where she practiced traditional earthenware methods that have been developed over centuries. The artist was fascinated by the division of labor at the factories, where men do the more toxic work and women concentrate on the ornamentation of the vessels and tiles. Issa’s wall-based works are sometimes hand-painted in the Iznik technique and based on traditional tiled surfaces, which are inherently grids typically found in architectural or domestic sites. In the twentieth century, Minimal Art often adopted the grid, which may be read as a Utopian form with its egalitarian dimensions and the possibility of extending into infinity. Artists including Sol Lewitt and Agnes Martin often utilized grids in their practice, which was intended to be purely formal and lacking in narrative. Issa takes this practice into new territory, disrupting the utopian notion of the grid by inserting cultural themes and commentary through the logos and the bleaching process.

Issa has a large mood board for her MFA thesis on her studio wall. Reproductions of architectural details, art nouveau furniture, faded advertisements on buildings, and shelves of ceramics hang side by side like a lexicon of images that inspire the artist. On a reproduction of Hank Willis Thomas’s Head 2003 photograph, which shows a black bald head with Nike tick on its surface, Issa scribbled on this the words “violence, cold, capitalism, brand intervention”. Her work, like that of Willis Thomas, critiques culture from within it, using the iconic brand language that is ubiquitous in our culture. In Issa’s practice she appropriates both traditional fine and decorative arts as well as popular culture seamlessly, revealing to the viewer how these brands are involved in racial and historical blanching.

Kathy Battista, 2023